Frank O’Hagan

A dedication

Up to the time of her death, a beloved sister of mine was a teacher for more than 40 years, working almost exclusively with pupils from deprived backgrounds or those experiencing social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. When she started her teaching career in the 1960s there was such a shortage of teachers that her very large primary class had to be divided into two groups. On alternative weeks, one group attended a morning session and the other an afternoon session. Both groups were considerably larger than the average primary class of to-day. While bravely facing her imminent death, she still worried about young persons’ future lifestyles and lack of learning opportunities. Sadly, many of her fears have morphed into a reality – continuing austerity, low levels of literacy, feelings of alienation and a lack of employment prospects. As I jot down my views on diversity, equity and inclusion, my gratitude goes to her and the many teachers, educational psychologists and inspectors of education who have contributed to improvements in this field and with whom I have had the privilege to work.

The times are always a-changing

In recent years, although there have been changes for the better, concern about services for vulnerable pupils with diverse needs – who live amidst all sectors of society – continues to be a debated and disquieting issue for parents and educationalists. What is more, in periods of hardships and public cutbacks, this aspect of educational provision for our more disadvantaged students can be seen as an easy target for financial constraint and staff reductions. A range of workable strategies will be necessary to ensure that so many young people do not come to perceive themselves as enduring failures.

Everyday attitudes about the characteristics of young learners alter and transmute, as do conventional stances regarding how their education should be subsidised and managed. These modifications are due to many different factors such as the impact of research projects, developments in teaching methods and advances in society’s views about the rights of children. Outlooks have evolved and perceptions have become more nuanced in a variety of ways. For instance, autism was once considered to be a very rare, one-dimensional and rather inexplicable disability. Nowadays, it is generally recognised as being much more prevalent and to be across an extensive and complex spectrum which comprises intellectual, linguistic, social and behavioural dimensions. Moreover, it is not unusual for pupils who have been assessed as on the autistic continuum to possess high levels of concentration and/or an in-depth comprehension concerning specific topics of interest. Additional cultural swings have included a greater acknowledgement of the potential of many learners displaying attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to demonstrate positive cognitive features such as creativity.

There are many promising means of developing suitable and empathetic contexts which are truly beneficial for all young people. Through well-tailored, personalised learning programmes, recent findings in educational neuroscience have provided a more hopeful perspective on the capacity of students to adapt to the difficulties which they encounter. Thankfully, there is an evident willingness among professionals to face the very significant obstacles which have to be overcome.

The message is clear that ability is not a fixed entity and that pessimistic attitudes about capabilities regularly need to be confronted. Nonetheless, key questions remain. Has society the will and capacity to address issues relating to diversity, equity and inclusion? How can plans be focussed on success while retaining inbuilt flexibility and identifiable care? Can educational systems have targeted interventions available to ensure that any apparent ‘breakdowns’ in levels of accomplishments can be quickly ameliorated?

Current challenges to inclusiveness

It is well nigh impossible to be unaware of the presence of diversity in modern society. It manifests itself in statistical surveys and in traditions and pretexts covering age, background, gender, ethnicity, ability, religion and so forth. It is our human melting pot containing both splendour and richness. It also can give rise to apprehension and unease has when individuals or groups are viewed as ‘others’ who are not fully entitled to the rights and privileges enjoyed by ‘in’ groups (a process sometimes referred to as ‘othering’).

Values – such as acceptance, appreciation and kindness – are elements of daily living to be treasured in education and training. Meeting the needs of diverse groups implies interconnectedness and cooperation in establishing universal rights and in building an equitable society. This stance calls for an end to greed, unrestrained capitalism and the continued destruction of Mother Earth. It stipulates that the voices of all students concerning their feelings and self-identified needs should not only be heard but be listened to attentively. Undoubtedly, there exist across our troubled world many obstructions to this vision which require urgent reform. Among an extensive list, depending on customs and place, it may be the disregard of the rights of children who are forced to work rather than be educated, the underachievement of poorer white male adolescents, or vocational openings being denied to students who are physically disabled.

Difficulties encountered, when teaching young persons with varying needs, are too often viewed as arising ‘from within’ or ‘belonging to’ them. From such perspectives, recognised learning problems can be treated as if they are owned by students and their private responsibility. Highly significant environmental factors – prejudices, the lack of adequate nutrition, impoverishment – are overlooked. Consequently, learners are not properly involved in decision-making but are subjected to pronouncements which are hoisted on them by way of a hierarchical system. Parents and guardians, due to their prior experiences, also can feel excluded and may need encouragement to build trust and become actively involved in combatting inequalities.

Skilled educationalists realise that many young people require basic but essential assistance in ‘learning how to learn’ in order to ensure future progress. Staff dedicated to inclusivity will have an expertise in: (1) creating warm and stimulating climates to facilitate headway; (2) establishing purposeful learners’ plans; (3) setting short- and long-term targets; (4) applying procedures relating to advice, guidance and support; and (5) providing motivational feedback to students, parents, guardians and other relevant parties. When acquired, pertinent skills – listening, collaborating, planning, problem-solving and coping mechanisms – can be transferred across curricular areas. It is critical that, for the prerequisites and characteristics of high-quality learning and teaching to be maintained, the capability and proficiency of staff are constantly upgraded through on-going professional development.

Every learner has the right to be included

All pupils deserve to be deemed worthy of making advancements at their own levels of attainment and capacities to learn. Various forms of integration have been implemented, for instance in terms of: locations; social arrangements and communal involvement; and functional and/or instructional settings. Genuine inclusive educational environments will fuse all such approaches into a cohesive and harmonious framework from which no student is excluded. Further, they extend to cover equitable opportunities for vocational training, employment placements and lifelong learning. The overriding philosophy must leave behind a previous ‘What are your problems and weaknesses?’ way of thinking and adopt an outlook which asks ‘In what ways can we assist you to enrich your attributes and extend your talents?’ Staff endorsing an all-encompassing ethos do not see themselves as working in ‘examination factories’. If necessary, they are willing to have fewer or no public accolades as regards their rankings in ‘fake’ national league tables.

When approaches to education are focused on the identified requirements of each learner, travel along productive and rewarding pathways to success is augmented. Along with this methodology, inclusiveness can be a strong catalyst in bringing about camaraderie among students of varying abilities and aptitudes. It follows that, if possible, they should not be cut off and isolated from their peers when undertaking tasks. Learners with diverse needs can expand their knowledge and skills fruitfully in hospitable pedagogic cultures. Authentic collegiate learning provides a sound basis for the cross-fertilisation of views on how they can assimilate information and benefit from new strategies on route to further accomplishments.

For educationalists to play an effective role, they have to challenge the status quo and provide the means of developing competences to overcome social and economic hardship. Programmes which cultivate both worthwhile qualities (for example, confidence, self-esteem, honesty and resilience) and relevant know-how (healthy living, money management, occupational capabilities and so forth) to enhance future chances are of the utmost importance. For these purposes, information and communication technology is helpful in nurturing learning and teaching and in addressing differing needs. At present, computer-based learning, though often very advantageous, is not a panacea. However, further innovations, as the quality of the machine-learner interface improves, augur high prospects.

All forms of educational provision require having well-defined roles, responsibilities and protocols in place for staff who are expected to respond to vulnerable students exhibiting risky behaviours, such as substance abuse, self-harm or noteworthy learning difficulties. Circumstances might necessitate the input of professional agencies which have clear remits to contribute at whole-school, group or individual levels of involvement. Short-term targets may focus on speedy improvements in attaining specific competences, expedited by time-limited, solution-based approaches to resolving pressing concerns. Longer-term objectives could embrace the acquisition of interpersonal skills and a sense of self-assurance. Indeed, for all, it is fitting to move forward well beyond existing hindrances and to encourage positive and rewarding lifestyles.

The dangers of labelling and classification

The drawbacks of labelling can include obscuring learners’ needs, making unwarranted assumptions about their abilities, and inadvertently depriving them of occasions to engage in inclusive practices. Labels also may have a negative impact on the confidence of teachers who might come to the erroneous conclusion that a pupil’s requirements and capacities cannot be accommodated at their school. Improved appliance of assessment methods can detect the co-existence of differing cognitive and behavioural difficulties, all of which require to be addressed within carefully-organised modes of intervention.

Teachers and educational psychologists wish to ascertain strengths and requisites when assessing learners. Unfortunately, by engaging in a classification process they may unwittingly fabricate a rationale which results in pupils being even further removed from mainstream education. For instance, students can suffer a ‘triple whammy’ as when a categorisation unduly influences: (1) low expectations relating to their potential; (2) an assumption that they should not be accepted into a school; and (3) the likelihood of them being permanently excluded.

There has been a widely-held belief that categorisation and labelling are important in providing legal protection, acquiring funding and gaining access to extra assistance from services and educational establishments. Certainly, case studies to back this view can be found. Nonetheless, there are other ways in which these benefits could be obtained if a comprehensive framework of students’ rights was utilised.

Endeavouring to fit an individual’s needs into a single grouping can have deleterious consequences. In general, there has been a distinct move away from the usage of tight categories. However, even looser eclectic descriptions, such as ‘experiencing additional support needs’, carry with them the danger of being interpreted as a rigid classification. A constant emphasis on differences and a disregard of similarities opens the way to shifting from receptive towards restricted mentalities. Vigilance to ensure that a learner is not excluded (or should one say ‘imprisoned’?) via the improper use of a label is paramount. (In any case, do we not all have additional needs, albeit diverse ones at differing levels?)

Assessment which leads to well-directed assistance and incentives

Appropriate appraisal procedures are required to address difficulties and play a crucial role on behalf of learners who are experiencing them. They not only clarify levels of current competences and capabilities but also indicate which forms of involvement and aid are most advantageous. In erstwhile routines, a great deal of credence was given by professionals to formal intelligence tests and standardised results in connection with language and numeracy. More recently, there have been considerable criticism and scepticism concerning the application of such types of normative measures. Very often, as an alternative, the emphasis has been placed firmly on using assessment techniques to help structure and maintain successful tutoring strategies, adaptive behavioural interventions and uplifting learning environments.

There is much to recommend in utilising processes which combine accurate assessments of strengths and requirements alongside the identification of those circumstances best suited to needs. Carefully-staged observations of everyday situations are valuable in avoiding simplistic analyses when attempting to map out how best to intervene. Within therapeutic and educational surroundings, formative assessment can be highly beneficial in terms of promoting both effort and achievements. It enables teachers to highlight what learners have mastered already and to devise future learning pathways.

Skills relating to on-going constructive assessments may appear easy on paper but in practice require substantial expertise. They take account of: devising and setting realistic objectives for all students; sympathetically but rigorously monitoring their progression; providing feedback in an inspirational manner; and collaborating with learners in reviewing their aspirations and in planning forthcoming goals. A concerted engagement following this outline reveals hidden talents, rejects segregation and increases a sense of belonging.

Conclusions

The needs of too many students are frequently missed, their perspectives misunderstood and their voices ignored among the bureaucratic and complex demands of modern education. A cultural shift is fundamental if inclusiveness is to gain traction. The acceptance of diversity and the commitment to ensuring equity for all entail high levels of advocacy, respect, tolerance, compassion and appreciation to permeate throughout learning communities. Unconscious bias has to be recognised and abolished along with negative stereotyping and labelling. Specialised support should be extended and focused within mainstream education, if necessary, using existing special schools and clinics as resource centres.

Governmental and local authority guidelines must wholeheartedly incorporate egalitarian principles and values. If official proposals or prescribed curricular topics prove to be unworkable, the duty of educationalists is to draw attention to deficiencies and to recommend or ‘reclaim’ appropriate courses of study and training programmes for their students. Schedules which include thoughtful and regular monitoring to enhance emotional wellbeing, acknowledge accomplishments and generate further advancement are key ingredients in maintaining successful developments. When effectively delivered, professional collaboration promotes confidence, self-belief and ‘can do’ mindsets regarding endless options for personal, social and intellectual growth.

In summary, proponents of inclusive education aspire to foster welcoming, coherent and vibrant systems which:

- are open and respectful to all learners without any imagined or created barriers to admission and full participation

- provide individualised learning pathways which ensure meaningful progress irrespective of identity, attributes and social background

- encourage students to take responsibility to attain their desired learning outcomes through well-planned and accommodating interchange and negotiation

- offer a comprehensive and integrated range of counselling, guidance and supportive strategies in conjunction with relevant professional agencies and local facilities

- help to build and maintain energetic, equitable and flourishing national and community services.

Appendix

Points for consideration

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal No 4: ‘To ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’ (by 2030).

United Nations: Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: General comment No 4, 2016. Article 24: Right to inclusive education: ‘The right to inclusive education encompasses a transformation in culture, policy and practice in all formal and informal educational environments to accommodate the different requirements and identities of individual students, together with a commitment to remove barriers that impede that possibility.’

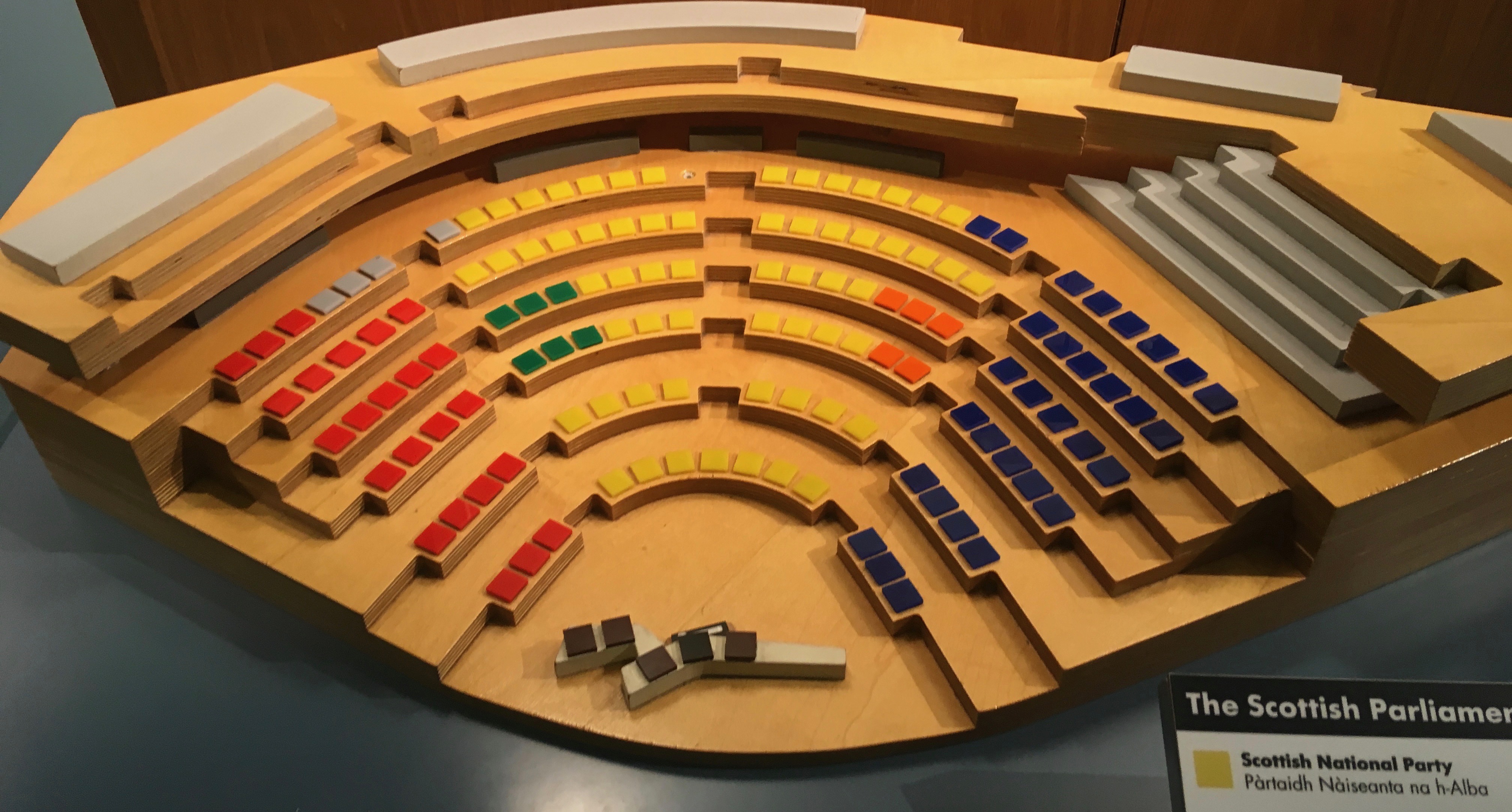

These are world-wide challenges. How advanced is our nation in reaching these high standards? Perhaps, more basically, are those in positions of power and responsibility fully aware of goals to which they are committed?

Note: For a brief charter focusing on the principles and characteristics of equity and inclusion in education, please use the following link: https://improvingcareand.education/home/inclusion-and-equity-in-education-key-principles-and-characteristics/

Additional note: Frank’s own blog covers social care and education, you are recommended to check it out at this link: https://improvingcareand.education

UNESCO’s Global Educational Monitoring (a true GEM!) Report 2020 was themed on Inclusion and Education. It now provides the new agenda for changes in education systems and schools towards inclusive education across the world. The impact of COVID-19 has been universal across the globe leading to globalised crisis in education that then impacts on specific groups to amplify inequalities. The GEM Report 2020 provides the roadmap into transformative change of education and schools for all.

UNESCO’s Global Educational Monitoring (a true GEM!) Report 2020 was themed on Inclusion and Education. It now provides the new agenda for changes in education systems and schools towards inclusive education across the world. The impact of COVID-19 has been universal across the globe leading to globalised crisis in education that then impacts on specific groups to amplify inequalities. The GEM Report 2020 provides the roadmap into transformative change of education and schools for all.

And so it began.

And so it began.