Just to continue with marking the publication of the Warnock report in May 1978. Its first chapter provided the history of segregated and special schools in the UK from the 18thcentury. I have extracted the Scottish references for a brief history of segregated education in Scotland from the perspective of Deaf and disabled provision. It’s a cut and paste job with a couple of additions but I‘ve saved you doing it!

18thcentury – The first school for the DEAF in Great Britain was started by Thomas Braidwood in Edinburgh in the early 1760s. Mr Braidwood’s Academy for the Deaf and Dumb, as it was called, took a handful of selected paying pupils to be taught to speak and read. By 1870 a further six schools had been founded, including the first in Wales at Aberystwyth (1847) and Donaldson’s Hospital (now Donaldson’s School) in Edinburgh. (Donaldson’s sold their building in Edinburgh and moved out to Linlithgow in 2008.) These early institutions for the deaf; no less than those for the blind, were protective places, with little or no contact with the outside world. The education that they provided was limited and subordinated to training. Many of their inmates failed to find employment on leaving and had recourse to begging.

The Asylum for the Industrious Blind at Edinburgh was opened in 1793. Such institutions were solely concerned to provide vocational training for future employment, and relied upon the profits from their workshops.

19thcentury – In Scotland, the first establishment for the education of “imbeciles” was set up at Baldovan in Dundee in 1852 and later became Strathmartine Hospital. An institution for “defectives” was founded later in Edinburgh: it transferred to a site in Larbert in 1863 and is today the Royal Scottish National Hospital. The Lunacy (Scotland) Act of 1862 recognised the needs of the mentally handicapped and authorised the granting of licences to charitable institutions established for the care and training of imbecile children.

The Forster Education Act of 1870 (and the corresponding Education (Scotland) Act of 1872) established school boards to provide elementary education in those areas where there were insufficient places in voluntary schools. The Acts did not specifically include disabled children among those for whom provision was to be made, but in 1874 the London School Board established a class for the DEAF at a public elementary school and later began the training of teachers.

It was equally so with the BLIND. Two years after the Scottish Act 50 blind children were being taught in ordinary classes in Scottish schools. (Are we able to say that inclusive practices have a history of at least 140 years for the visually impaired being included in their local schools in Scotland?)

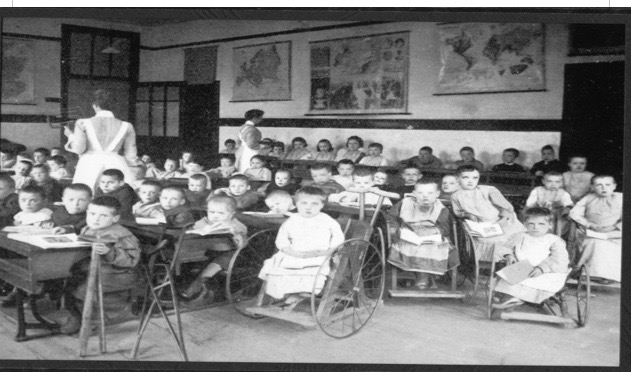

Special educational provision for PHYSICALLY AND MENTALLY HANDICAPPED children was even slower off the mark. Those who attended elementary schools profited as best they could from the ordinary teaching. The more severely handicapped received care and sometimes education in institutions.

In Glasgow in 1874, East Park was founded after the formation of “The Association for Visiting and Aiding the Permanently Infirm and Imbecile Children”. In 1874 children were admitted with paralysis, hip, spine and knee joint diseases with rickets being a widespread problem. The East Park cottage Home for Infirm Children was effectively a care institution managed by a superintendent and whose staff wore nursing uniforms.

A Royal Commission on the Blind and Deaf was constituted in 1886 and reported in 1889. Legislation quickly followed for Scotland in the Education of Blind and Deaf Mute Children (Scotland) Act of 1890, but three years elapsed before England and Wales were similarly covered by the Elementary Education (Blind and Deaf Children) Act of 1893. The Act required school authorities* to make provision, in their own or other schools, for the education of blind and deaf children resident in their area who were not otherwise receiving suitable elementary education. The new Act meant that all blind or deaf children would in future be sent to school as of right.

20thcentury- In Scotland, the Education of Defective Children (Scotland) Act of 1906 empowered school boards to make provision to special schools or classes for the education of defective children between the ages of five and 16, whilst the Mental Deficiency (Scotland) Act of 1913 required school boards to ascertain children in their area who were defective, and those who were considered incapable of benefiting from instruction in special schools became the responsibility of parish councils for placement in an institution. By 1939 the number of mentally defective children on the roll of special schools and classes had reached 4,871.

However, since maladjustment was not officially recognised as a form of handicap calling for special education, practically no provision was made by authorities for these pupils before 1944, although some authorities paid for children to attend voluntary homes.

In Scotland, the Education (Scotland) Act 1945 repeated much of the content of the Education Act 1944, but with certain important differences. The duty of education authorities to ascertain which children required special educational treatment applied to children from the age of five.

The Handicapped Pupils and School Health Service Regulations 1945 defined 11 categories of pupils: blind, partially sighted, deaf, partially deaf, delicate, diabetic, educationally subnormal, epileptic, maladjusted, physically handicapped and those with speech defects. Maladjustment and speech defects were entirely new categories. Partial blindness and partial deafness were extensions of existing categories, whilst delicate and diabetic children had previously been treated as physically handicapped. The categories (though not the detailed definitions) have remained unchanged since 1944 except that in 1953 diabetic children ceased to form a separate category and have since then been included with the delicate. The regulations prescribed that blind, deaf, epileptic, physically handicapped and aphasic children were seriously disabled and must be educated in special schools. Children with other disabilities might attend ordinary schools if adequate provision for them was available.

In Scotland an attempt was made to bring together expert opinion on all forms of handicap. In 1947 the Secretary of State remitted to the Advisory Council in Scotland the task of reviewing the provision made for the primary and secondary education of pupils suffering from disability of mind or body or from maladjustment due to social handicaps. The Council produced between 1950 and 1952 seven reports which were valuable guides to education authorities on the provision for different handicaps, although their predictions of future need have not all stood the test of time. For example, it was thought that special provision should be made for 20,000 physically handicapped pupils, whereas the number of these children in special schools in 1976 was only 1,076: conversely the Council’s estimate that four residential child guidance clinics would suffice to meet the needs of all children maladjusted because of social handicap has proved to be hopelessly inadequate.

The Scottish Education Department Circular No 300 (The Education of Handicapped Pupils: The Reports of the Advisory Council (21 March 1955).

The titles of the Reports were as follows:

Pupils who are Defective in Hearing (Cmd 7866)

Pupils who are Defective in Vision (Cmd 7885)

Visual and Aunt Aids (Cmd 8102)

Pupils with Physical Disabilities (Cmd 8211)

Pupils with Mental or Educational Disabilities (Cmd 8401)

Pupils handicapped by Speech Disorders (Cmd 8426)

Pupils who are Maladjusted because of Social Handicap (Cmd 8428)

in presenting these reports they placed special education within the mainstream of primary and secondary education.

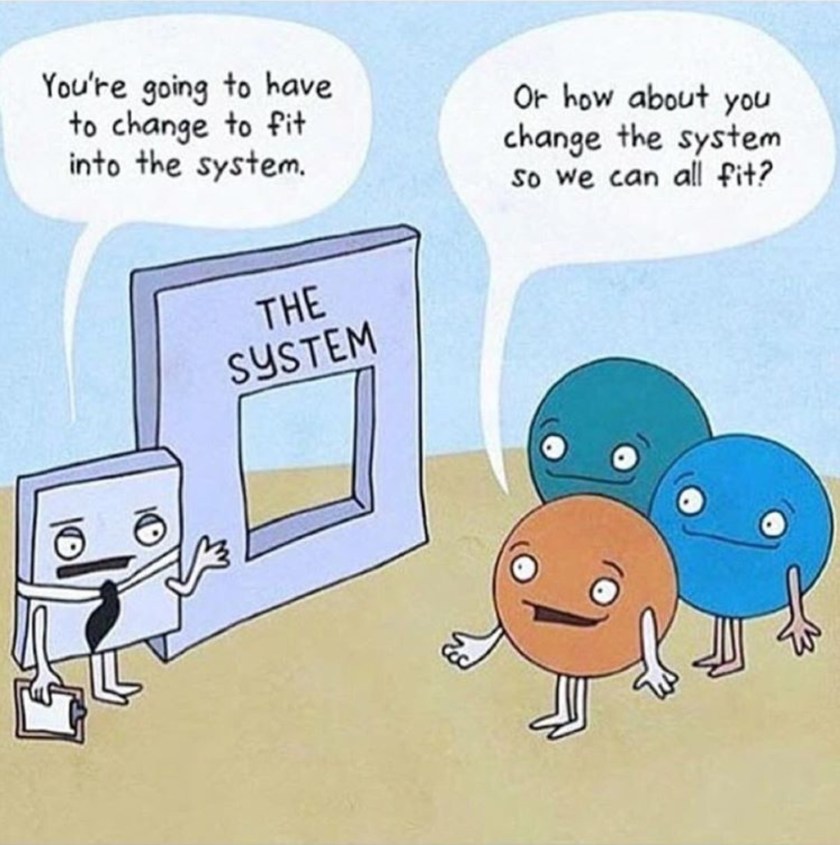

“Special educational treatment should not be thought of mainly in terms of the provision on a large scale of separate schools for handicapped children…. It is recognised that there must continue to be situations where it is essential in the children’s interest that those who are handicapped must be separated from those who are not. Nevertheless as medical knowledge increases and as general school conditions improve it should be possible for an increasing proportion of pupils who require special educational treatment to be educated along with their contemporaries in ordinary schools. Special educational treatment should, indeed, be regarded simply as a well-defined arrangement within the ordinary educational system to provide for the handicapped child the individual attention that he particularly needs.”

In the year prior to the issue of Circular No 300 Scottish regulations were made laying down definitions of the nine statutory categories of handicap. Delicate and diabetic children were not included as they were in England and Wales. These Regulations, together with the 1956 Schools Code, which prescribed maximum class sizes for the various categories of handicap, ensured for handicapped children in Scotland the benefit of favourable pupil-teacher ratios.

In Scotland education authorities became responsible in 1947 for the education of children who were described as “ineducable but trainable”. Those children were placed in junior occupational centres and trained by instructors, but following the Report of the Melville Committeeand subsequent provisions in the Education (Mentally Handicapped Children) (Scotland) Act 1974 the centres were re-named schools, and teachers were appointed in addition to the instructors. The 1974 Act also gave education authorities responsibility for the education of children who had previously been described as “ineducable and untrainable”.

In Scotland all the functions of the former approved schools, including the provision of education, were transferred in 1971 to local authority social work departments under the terms of the Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968, and these institutions are now known as List D schools.

In Scotland the 1960s had seen some confusion over the procedures for the assessment of handicapped children. Working parties examined the assessment of four groups of handicapped children: mentally handicapped, visually handicapped, maladjusted and hearing impaired. As a result major procedural changes were included in the Education (Scotland) Act 1969. The Act redefined special education in terms which excluded the concept of a fixed disability of mind or of body. It recognised the importance of early discovery by abolishing the minimum age at which a child could be ascertained by an education authority and established that the decision to ascertain a child was not exclusively a medical one. It required that in every case reports of psychological as well as medical examinations should be considered, with, wherever possible, the views of the child’s parents and those of his teacher. It also recognised the widely held view that assessment is a continuing process.

In Scotland, the same theme lay behind the report of the McCann Committee on the secondary education of physically handicapped children. (The Secondary Education of Physically Handicapped Children in Scotland. Report of the Committee appointed by the Secretary of State for Scotland (HMSO, 1975). ) The Committee’s report, whilst recognising that some physically handicapped children would require education in special schools, envisaged an ever increasing number of them being educated in ordinary schools.

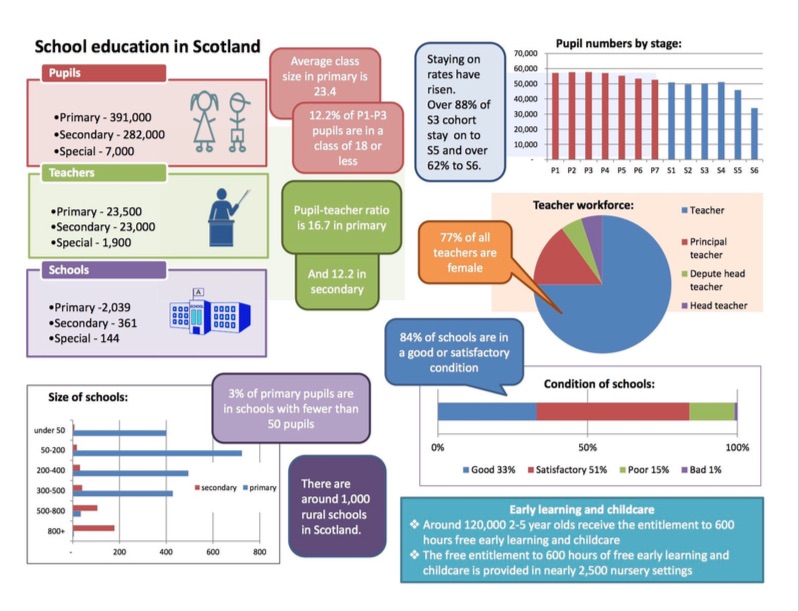

The extent of special educational need is very difficult to assess. Some indication is given by the figures for the children ascertained as requiring special education IN THE TRADITIONAL SENSE OF SEPARATE SPECIAL PROVISION. In Scotland 15,119 children or 1.4% of the school population were receiving separate special educational provision in the session 1976-77. However, this scale on which children are ascertained as being in need of special education varies widely from one authority to another.

In Scotland in the 1975-76 session the prevalence of children receiving special education ranged from 50 per 10,000 of the school population in a rural region to over 200 in a region with a large conurbation. Four out of nine regions were within a range 10% above or below the national average of 120.Some of the variations between authorities may reflect variations in local policy and the strength of assessment services, but they also suggest a relationship between the rate of ascertainment and the availability of special provision. It is to be noted that this level is approximately the same in 2018 as in 1976!

The definition of special education in the Education (Scotland) Act 1969, although it has the merit of using terms which clearly apply to children with emotional or behavioural disorders as well as those with physical or intellectual disabilities, is similarly negative in tone: “education by special methods appropriate to the requirements of pupils whose physical, intellectual, emotional or social development cannot, in the opinion of the education authority, be adequately promoted by ordinary methods of education”. Such a definition conveys nothing of the qualities or features which make special education “special”.

That’s you nearly up to date. After Warnock, in Scotland there were a range of reports on good practice culminating in the Inspectorate review of special schools in 2002.

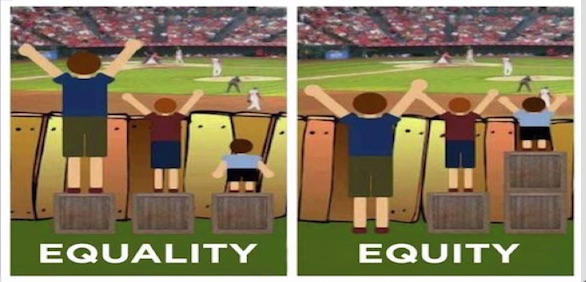

To each according to their needs

To each according to their needs

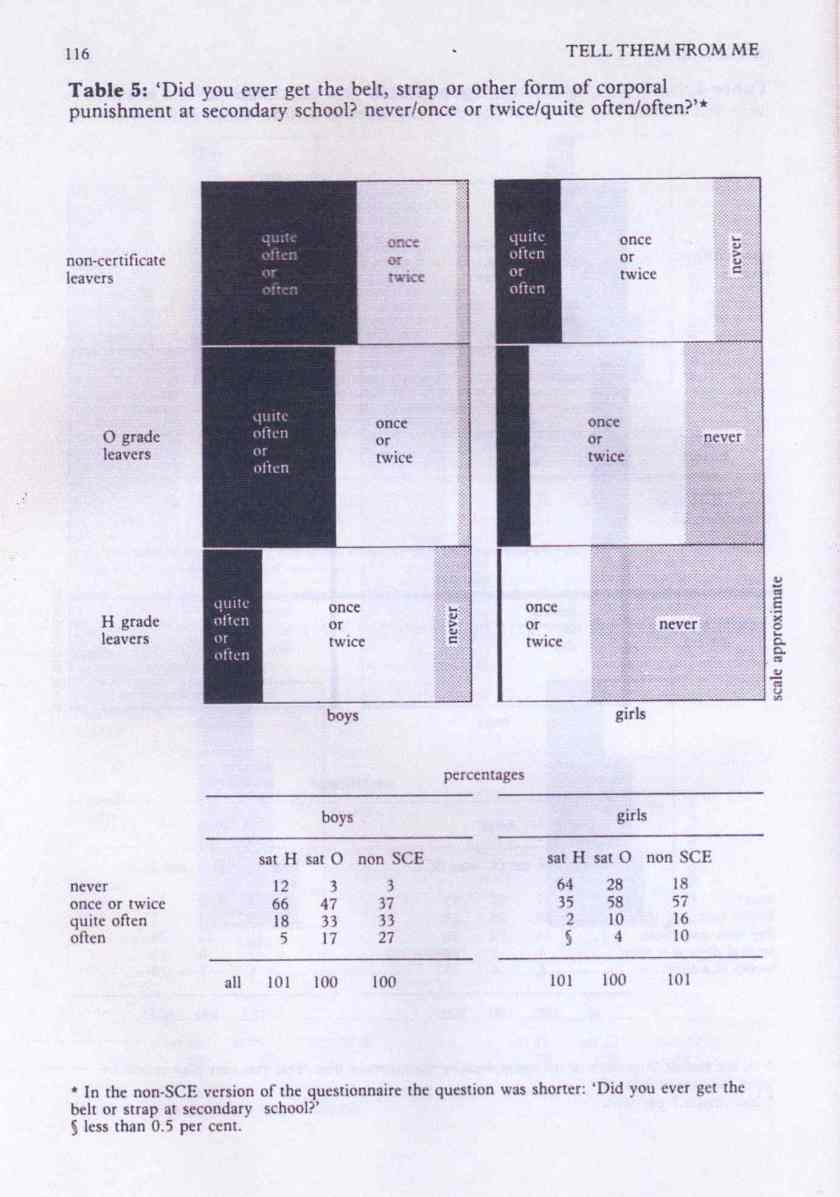

Since then we have transformed our schools from punishment regimes to more supportive, inclusive spaces where positive relationships are at the heart of practice. Accompanying this transition has been a shift in the well being of young people and following that improvement their behaviour and relationships with others.

Since then we have transformed our schools from punishment regimes to more supportive, inclusive spaces where positive relationships are at the heart of practice. Accompanying this transition has been a shift in the well being of young people and following that improvement their behaviour and relationships with others.