Visuals travel faster than the speed of words and even without a thousand words, images show their worth in communicating ideas.

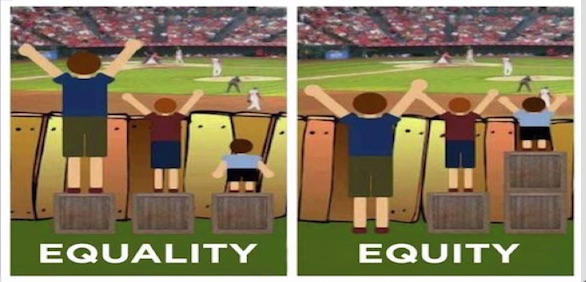

The above image of the young people peering over fences at a baseball game has been given great a currency over the past few years.

You can read about how it came about in December 2012 by Craig Froehle. He originally created the graphic to make the point between equality of opportunity and equality in outcomes in a debate with a conservative during USA 2012 election. He modestly describes his creative process as:

“So, I grabbed a public photo of Cincinnati’s Great American Ball Park, a stock photo of a crate, clip art of a fence, and then spent a half-hour or so in Powerpoint concocting an image”

His graphic must have been used in thousands of presentations as a simple and effective way to push the debate in politics or social services or education towards fairness rather than opportunity.

In the first panel of the graphic all the young people have the opportunity to look at the ball game but not everyone has a successful outcome. The second panel then displays a fairer outcome. Someone once said something about “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” and the image has something of that.

Of course I have to admit I was one of those young people outside the fence in my youth. On occasion my brothers trying to see the game at a junior football ground in the West of Scotland. We never achieved the equitable outcome because usually we found a way to sneak in by climbing over the fence.

There is another website (Cultural Organizing) that offers a critique of the graphic in its various forms describing it as perfect example of deficit thinking. (By the way they describe the removing of the fence to get in for free as a “creative and subversive” response – we called it duking in).

A final website lets you design your own third and even fourth panel. It again looks at some different versions and lets you design a fourth box (the 4th box) for the cartoon.

Then there is the short youtube version for younger children called Fairness set away from sports fields. Again three children this time picking apples from a tree and sharing boxes to stand on. There may well be a feature film coming some time soon.

In education terms many schools and teachers are keen to assert that they treat everyone the same. People on the first box never readily give up that privilege they feel they deserve with that resource. Whether you view that first box as private schooling, the over emphasis and weighting towards gaining entry to University and streamed or set classes. All of those “crates” are supports that reinforce inequity and not readily yielded.

More debate and discussion about equitable outcomes needs to consider the second panel and celebrate ways that give the support to those that need it, children and young people from working class backgrounds, care experienced young people and those with disabilities. It also requires decisions from the first panel about which “crates” need reallocated.

To each according to their needs

To each according to their needs